Today’s Photo Tip: Understanding ISO. One of the three pillars of photography referred to as the “Exposure Triangle” (the other two being Aperture and Shutter Speed), every photographer needs to thoroughly understand ISO to get the most out of their equipment. It's one of the most prominently featured specifications of any modern digital camera, and it's one single aspect that can make a night-and-day difference in the outcome of your shots. Click here to read this photo tip … Understanding ISO. Today’s Photo Tip: Understanding ISO. One of the three pillars of photography referred to as the “Exposure Triangle” (the other two being Aperture and Shutter Speed), every photographer needs to thoroughly understand ISO to get the most out of their equipment. It's one of the most prominently featured specifications of any modern digital camera, and it's one single aspect that can make a night-and-day difference in the outcome of your shots. Click here to read this photo tip … Understanding ISO. |

Wednesday

Journal Entry for Wednesday, July 28th

Sunday

Journal Entry for Sunday, July 21st

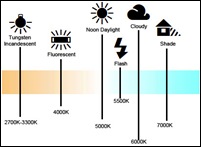

Today’s Photo Tip: If you’re one of those photographers that still leave the white balance selection on your camera set to the AWB (automatic white balance), you need to read this photo tip. Learning what white balance really is and how to properly use this control can have a profound effect on your photos. What you don't know about white balance can kill an image. Click here to learn more about White Balance … Understanding White Balance. Today’s Photo Tip: If you’re one of those photographers that still leave the white balance selection on your camera set to the AWB (automatic white balance), you need to read this photo tip. Learning what white balance really is and how to properly use this control can have a profound effect on your photos. What you don't know about white balance can kill an image. Click here to learn more about White Balance … Understanding White Balance. |

Saturday

Today’s Musing - Digital Camera Sensor Size

Thinking about buying a high-end digital camera? Purchasing a quality digital camera today can be a daunting experience. Similar to the cellphones, tablets and laptops, advances in the technology for making cameras and lenses is moving so rapidly, it makes zeroing in on a purchase seem like you are selecting a moving target. However, regardless of the type and style of camera you choose, or its feature set, the one single factor that determines a camera’s ability to capture great pictures is the size of its digital sensor. Hopefully this post will help you to better understand this all important feature and the options available to you. Check it out here … Digital Camera Sensor Size. Thinking about buying a high-end digital camera? Purchasing a quality digital camera today can be a daunting experience. Similar to the cellphones, tablets and laptops, advances in the technology for making cameras and lenses is moving so rapidly, it makes zeroing in on a purchase seem like you are selecting a moving target. However, regardless of the type and style of camera you choose, or its feature set, the one single factor that determines a camera’s ability to capture great pictures is the size of its digital sensor. Hopefully this post will help you to better understand this all important feature and the options available to you. Check it out here … Digital Camera Sensor Size. |

Monday

Journal Entry for Sunday, July 14th

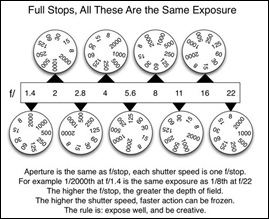

Today’s Photo Tip: It seems that I am always struggling with making the proper aperture settings on my camera when trying to achieve specific results. If you have ever tried to make use of the manual aperture settings on your camera, and are anything like me, I’m sure you have had some of the same problems. For me, I think it is due in part to the fact that the whole classification of f/stops seems contrary to logic; e.g. larger f/stops mean smaller openings and smaller f/stops mean larger openings. As a result, I began an Internet search for pages on aperture, looking for information that would help me to better understand it. After reading numerous pages, I attempted to boil down everything I read into simple, everyday language, and create a page that I could use to refresh my memory as needed, until all of the information becomes imbedded into my sometimes thick scull. Here is the result … Understanding Aperture. I hope you find it helpful. Today’s Photo Tip: It seems that I am always struggling with making the proper aperture settings on my camera when trying to achieve specific results. If you have ever tried to make use of the manual aperture settings on your camera, and are anything like me, I’m sure you have had some of the same problems. For me, I think it is due in part to the fact that the whole classification of f/stops seems contrary to logic; e.g. larger f/stops mean smaller openings and smaller f/stops mean larger openings. As a result, I began an Internet search for pages on aperture, looking for information that would help me to better understand it. After reading numerous pages, I attempted to boil down everything I read into simple, everyday language, and create a page that I could use to refresh my memory as needed, until all of the information becomes imbedded into my sometimes thick scull. Here is the result … Understanding Aperture. I hope you find it helpful. |

Journal Entry for Monday, July 8th

|

|

Saturday

Recent Purchase - Joby JM1-01WW GripTight Mount

Joby JM1-01WW GripTight Mount (Black): The perfect holder for any smartphone, any tripod, anywhere! This is the only tripod mount that supports all the best-selling smartphones, with or without a protective case. It is compatible with GorillaPods™ and other tripods via a universal stainless steel ¼"-20 thread. The GripTight Mount stabilizes and positions your smartphone to give you steady video and crisp photos from new perspectives. It is designed with a durable steel inner frame and rubber grip pads that holds your phone in place, even when rotated sideways or upside down. Furthermore, it is fold-able and portable. The legs fold in making it easy to fit it in your pocket or bag. you can also attach a lanyard to it and add it to your key chain so it's always with you. Joby JM1-01WW GripTight Mount (Black): The perfect holder for any smartphone, any tripod, anywhere! This is the only tripod mount that supports all the best-selling smartphones, with or without a protective case. It is compatible with GorillaPods™ and other tripods via a universal stainless steel ¼"-20 thread. The GripTight Mount stabilizes and positions your smartphone to give you steady video and crisp photos from new perspectives. It is designed with a durable steel inner frame and rubber grip pads that holds your phone in place, even when rotated sideways or upside down. Furthermore, it is fold-able and portable. The legs fold in making it easy to fit it in your pocket or bag. you can also attach a lanyard to it and add it to your key chain so it's always with you. Even though I have never been one for taking many pictures with my phone, I have begun to realize that this seems to be where the trend in picture taking is headed. With higher mega-pixel resolution cameras on phones, due to rapidly Increasing technologies in the areas of smaller camera censors, smaller lenses, more powerful memory chips, and a vast array of post editing software for phones has made picture taking with a phone almost a violable option for obtaining quality pictures. Today there are an overwhelming number of photo related apps to help edit, enhance, and share pictures, and while in-phone editing can be convenient and fun, there is always the ability to download the pictures to a computer for post editing with a full version of Adobe Photoshop, or other editing software, opening up many possibilities like layer masking, unsharp mask, noise reduction, and more. For example, my new Samsung Galaxy S4 has a 13-Megapixel auto-focus camera that allows you to simultaneously take pictures with both its front and (2MP) rear camera. This is 12x the megapixel count of my first handheld digital camera, an Olympus D450 1.2MP Digital Camera w/ 3x Optical Zoom that cost nearly $300. Check out my tips for taking pictures with a cell-phone camera …. Tips for Taking Better Cell Phone Pictures. |

Wednesday

Category Description

Whenever I figure out the answer to a problem or find some bit of information that has been helpful to my personal photographic experiences, I try to make a point of posting the solution or tip at the bottom of one of my daily postings or as a separate photo tip. I created this page to act as a collection point for all of these tips. If you are looking for more help and tips, I have also listed some of my favorite Internet sites in the References tab found at the top-right of each page. Click the tab (and the links therein) to see more.

PLEASE NOTE: Any specific references to camera buttons, settings, mode dials, menus, displays, etc. are all based upon the two cameras that I use; a Panasonic Lumix DMC-G2 Micro Four Thirds camera, and a Panasonic LUMIX DMC-ZS19. (Click the My Equipment tab above for more details) Though the elements described may be somewhat different from manufacturer to manufacturer, they are quite often very similar. Most of the time you should be able to equate the reference to your specific camera without too much trouble.

PLEASE NOTE: Any specific references to camera buttons, settings, mode dials, menus, displays, etc. are all based upon the two cameras that I use; a Panasonic Lumix DMC-G2 Micro Four Thirds camera, and a Panasonic LUMIX DMC-ZS19. (Click the My Equipment tab above for more details) Though the elements described may be somewhat different from manufacturer to manufacturer, they are quite often very similar. Most of the time you should be able to equate the reference to your specific camera without too much trouble.

Tuesday

Index for the Category - Photography Tips

Index for Category - Photographic Musings

Click on a Title Below to Read

|

Index for Category - Picture Editing Tips

Monday

Understanding Aperture

Understanding Light: Photography is not about selecting buttons and switches on a highly sophisticated piece of electronic and optical equipment; photography is about seeing the light. Without light, there is no photograph; end of story. Light controls what you see in a photograph and how you see it. Understanding Light: Photography is not about selecting buttons and switches on a highly sophisticated piece of electronic and optical equipment; photography is about seeing the light. Without light, there is no photograph; end of story. Light controls what you see in a photograph and how you see it.  Aperture, which is measured by f/stops, controls the volume of light passing through your lens. Controlling the intensity of light as it passes through the lens (opening) and onto the camera’s electronic sensor (or film) is what aperture is all about. There are only two other mechanisms used for controlling light, filters and shutter speed. The chart above shows how the amount of light is decreased as the f/stops increase in "full" f/stops. Increasing the f/stop numbers to reduce the amount of light passing through the lens is known as “stopping down” the lens. In contrast, decreasing the f/stop numbers to double the amount of light that is passing through the lens, is known as "opening up" the lens. Aperture, which is measured by f/stops, controls the volume of light passing through your lens. Controlling the intensity of light as it passes through the lens (opening) and onto the camera’s electronic sensor (or film) is what aperture is all about. There are only two other mechanisms used for controlling light, filters and shutter speed. The chart above shows how the amount of light is decreased as the f/stops increase in "full" f/stops. Increasing the f/stop numbers to reduce the amount of light passing through the lens is known as “stopping down” the lens. In contrast, decreasing the f/stop numbers to double the amount of light that is passing through the lens, is known as "opening up" the lens. |

Lens Aperture & Identification: Every lens has a limit on how large or how small the aperture can get. The maximum aperture of the lens is much more important than the minimum, because it shows the “speed” of the lens. The f/number is the focal length of the lens divided by virtual aperture (the circle you see when looking through the back end of a lens. Every lens is designated by its LARGEST opening (smallest f-number) e.g. 50mm f1/4. BIGGER numbers (f/16, f/22) specify a SMALL aperture (lens opening) that admits LESS light. SMALLER numbers (f/2, f/2.8) indicate a LARGER aperture (lens opening) that admits MORE light. Lens Aperture & Identification: Every lens has a limit on how large or how small the aperture can get. The maximum aperture of the lens is much more important than the minimum, because it shows the “speed” of the lens. The f/number is the focal length of the lens divided by virtual aperture (the circle you see when looking through the back end of a lens. Every lens is designated by its LARGEST opening (smallest f-number) e.g. 50mm f1/4. BIGGER numbers (f/16, f/22) specify a SMALL aperture (lens opening) that admits LESS light. SMALLER numbers (f/2, f/2.8) indicate a LARGER aperture (lens opening) that admits MORE light. |

The f/stop Scale: The first thing you need to know the f-stop scale. The scale is as follows: f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, f/22. The thing to know is that, from each number to the next, the aperture decreases to half its size and allows 50% less light through the lens. This is because the numbers come from the equation used to work out the size of the aperture from the focal length. You’ll notice, on modern day cameras, that there are apertures in between those listed above. These are1/3 stops, so between f/2.8 and f/4 for example, you’ll also get f/3.2 and f/3.5. These are just here to increase the control that you have over your settings. The f/stop Scale: The first thing you need to know the f-stop scale. The scale is as follows: f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, f/22. The thing to know is that, from each number to the next, the aperture decreases to half its size and allows 50% less light through the lens. This is because the numbers come from the equation used to work out the size of the aperture from the focal length. You’ll notice, on modern day cameras, that there are apertures in between those listed above. These are1/3 stops, so between f/2.8 and f/4 for example, you’ll also get f/3.2 and f/3.5. These are just here to increase the control that you have over your settings. |

| The zoom problem: Unless buying the “body only”, almost every camera, no matter how good the camera, comes with an inexpensive zoom lens. As you zoom the lens to a longer focal length, but maintain the same maximum aperture size, you end up with a larger f-number that results in a dimmer image. Zoom lenses that do this are called "variable-aperture zooms" and are designated with a hyphenated maximum aperture, e.g. an 18-55mm f/3.5-5.6. This means that you get f/3.5 when set to the maximum aperture of 18mm, but only f/5.6 when zoomed to 55mm. A "constant-aperture zoom lens” on the other hand will maintain the same f-number at all focal lengths when set manually. Such zooms, e.g.24-70mm f/2.8 Zoom Lens, are optically much more complex than variable-aperture zooms, resulting in a bulkier, heavier and more expensive lens. Because this type of lens allows you to capture better pictures in low light situations, and usually has more aperture blades that provide better “bokeh” (the wider the aperture, the narrower the depth of field), it is definitely worth the extra money. |

Setting the f/stop (aperture): Simply put, aperture is the hole within a lens, through which light travels into the camera body. The lower the f/stop number, the wider, or bigger, the aperture. Changing the aperture for a particular evenly-exposed shot means you need to shoot faster to compensate (or increase the ISO). This is because shooting faster reduces the amount of light going through the lens. This is the relationship between aperture and shutter speed. It is recommended that you only shoot in the Auto mode (where the camera makes all the decisions on settings) when circumstances dictate quick, responsive, shooting. Turning your camera’s Mode Dial to A or Av (which stands for Aperture value) means that you set the aperture you want and the camera compensates by making the decisions on shutter speed. This is a particularly good way of ensuring you achieve the DOF you want from your image, the other reason why a faster lens is desirable. Bokeh. The wider the aperture, the narrower the depth of field. Setting the f/stop (aperture): Simply put, aperture is the hole within a lens, through which light travels into the camera body. The lower the f/stop number, the wider, or bigger, the aperture. Changing the aperture for a particular evenly-exposed shot means you need to shoot faster to compensate (or increase the ISO). This is because shooting faster reduces the amount of light going through the lens. This is the relationship between aperture and shutter speed. It is recommended that you only shoot in the Auto mode (where the camera makes all the decisions on settings) when circumstances dictate quick, responsive, shooting. Turning your camera’s Mode Dial to A or Av (which stands for Aperture value) means that you set the aperture you want and the camera compensates by making the decisions on shutter speed. This is a particularly good way of ensuring you achieve the DOF you want from your image, the other reason why a faster lens is desirable. Bokeh. The wider the aperture, the narrower the depth of field. |

What is Depth of Field? The one important thing to remember is that the size of the aperture has a direct impact on the depth of field, which is the area of the image that appears sharp. A large f-number such as f/32, (which means a smaller aperture) will bring all foreground and background objects in focus, while a small f-number such as f/1.4 will isolate the foreground from the background by making the foreground objects sharp and the background blurry, creating what is commonly referred to as “bokeh”. What is Depth of Field? The one important thing to remember is that the size of the aperture has a direct impact on the depth of field, which is the area of the image that appears sharp. A large f-number such as f/32, (which means a smaller aperture) will bring all foreground and background objects in focus, while a small f-number such as f/1.4 will isolate the foreground from the background by making the foreground objects sharp and the background blurry, creating what is commonly referred to as “bokeh”. |

Setting Exposure: The optimum exposure for any given scene is comprised of four elements; light, shutter speed, aperture and ISO, the last three under your control are know as the "Exposure Triangle". There are two parts involved in exposing a digital sensor to light. One is the intensity of the light and the other is the length of time the light is allowed to strike the sensor. Exposure is the measure of how much light (the AMOUNT OF LIGHT controlled by the aperture) that is captured over a SPECIFIC AMOUNT OF TIME (controlled by the shutter speed), e.g. Exposure = Intensity x Time. Understanding the relationship between aperture and shutter speed and how to control them will take your photography to another level. Aperture and f/stop are indeed references to the same thing. The aperture is the lens mechanism and f/stop is the measure of mechanism’s engagement. Think of it this way; a properly exposed photo might need 1,000 "units" of light to hit the sensor. Your camera can do one of two things to ensure that 1,000 units hit the sensor: (1) it can open the shutter for more time - this is called the shutter speed. If opening the shutter for half a second lets in 500 units of light, doubling that to one second will let in the 1,000 units you need for a well exposed photo, (2) your camera can allow those 1,000 units in is to make the hole at the front of the camera wider (this hole is the aperture). The shutter speed can stay at half a second, but make the hole at the front of the camera twice as large and 1,000 units of light can enter in that same half a second. The longer the shutter is open, the longer the light has to expose the film, the shorter the shutter is open, the less time there is to exposed the film. Just remember that each full f/stop either halves or doubles the amount of light entering the camera and each full shutter speed stop either halves or doubles the amount of time of the exposure. It is possible to have the same exposure with a variety of different f/stops and shutter speeds depending on what effect you want to achieve. If you are in aperture priority and change the f stop the shutter speed automatically changes for a proper exposure; if you are in shutter speed priority and change the shutter speed the f/stop automatically changes for a proper exposure. Since you don’t have to manually change both factors of an exposure in these modes, many new photographers have a hard time understanding this relationship. Then there is ISO. While shutter speed and aperture determine how much light reaches the sensor, ISO relates to how the sensor reacts to that light. The higher the ISO, the more sensitivity and the greater the sensor's light gathering capacity; meaning that less light is needed to create the desired exposure. So I know you are now thinking, if my camera can automatically do this for me why should I care what my f/stop or shutter speed is? Because a knowledge of these concepts will allow you to determine the sharpness or depth of field given to a given area. If you let the camera do everything for you, you will only get average images. Setting Exposure: The optimum exposure for any given scene is comprised of four elements; light, shutter speed, aperture and ISO, the last three under your control are know as the "Exposure Triangle". There are two parts involved in exposing a digital sensor to light. One is the intensity of the light and the other is the length of time the light is allowed to strike the sensor. Exposure is the measure of how much light (the AMOUNT OF LIGHT controlled by the aperture) that is captured over a SPECIFIC AMOUNT OF TIME (controlled by the shutter speed), e.g. Exposure = Intensity x Time. Understanding the relationship between aperture and shutter speed and how to control them will take your photography to another level. Aperture and f/stop are indeed references to the same thing. The aperture is the lens mechanism and f/stop is the measure of mechanism’s engagement. Think of it this way; a properly exposed photo might need 1,000 "units" of light to hit the sensor. Your camera can do one of two things to ensure that 1,000 units hit the sensor: (1) it can open the shutter for more time - this is called the shutter speed. If opening the shutter for half a second lets in 500 units of light, doubling that to one second will let in the 1,000 units you need for a well exposed photo, (2) your camera can allow those 1,000 units in is to make the hole at the front of the camera wider (this hole is the aperture). The shutter speed can stay at half a second, but make the hole at the front of the camera twice as large and 1,000 units of light can enter in that same half a second. The longer the shutter is open, the longer the light has to expose the film, the shorter the shutter is open, the less time there is to exposed the film. Just remember that each full f/stop either halves or doubles the amount of light entering the camera and each full shutter speed stop either halves or doubles the amount of time of the exposure. It is possible to have the same exposure with a variety of different f/stops and shutter speeds depending on what effect you want to achieve. If you are in aperture priority and change the f stop the shutter speed automatically changes for a proper exposure; if you are in shutter speed priority and change the shutter speed the f/stop automatically changes for a proper exposure. Since you don’t have to manually change both factors of an exposure in these modes, many new photographers have a hard time understanding this relationship. Then there is ISO. While shutter speed and aperture determine how much light reaches the sensor, ISO relates to how the sensor reacts to that light. The higher the ISO, the more sensitivity and the greater the sensor's light gathering capacity; meaning that less light is needed to create the desired exposure. So I know you are now thinking, if my camera can automatically do this for me why should I care what my f/stop or shutter speed is? Because a knowledge of these concepts will allow you to determine the sharpness or depth of field given to a given area. If you let the camera do everything for you, you will only get average images.In Summary - Practice, Practice, Practice: The best way to improve your photography is to practice as often as you can. Always try to have your camera with you. Even when that is not possible, continue to look at your surroundings as if you were trying to create a photograph. Compose hypothetical shots in your mind by thinking about light and what settings you might use to achieve various effects. |

Understanding White Balance

Digital Camera Sensor Size

Thinking about buying a high-end digital camera? Purchasing a quality digital camera today can be a daunting experience. Similar to the cellphones, tablets and laptops, advances in the technology for making camera and lenses is moving so rapidly, it makes zeroing in on a purchase seem like you are selecting a moving target. However, regardless of the type and style of camera you choose, or its feature set, the one single factor that determines a camera’s ability to capture great pictures is the size of its digital sensor. Hopefully this post will help you to better understand this all important feature and the options available to you. Thinking about buying a high-end digital camera? Purchasing a quality digital camera today can be a daunting experience. Similar to the cellphones, tablets and laptops, advances in the technology for making camera and lenses is moving so rapidly, it makes zeroing in on a purchase seem like you are selecting a moving target. However, regardless of the type and style of camera you choose, or its feature set, the one single factor that determines a camera’s ability to capture great pictures is the size of its digital sensor. Hopefully this post will help you to better understand this all important feature and the options available to you. | |

Understanding Sensor Size: The size of sensor that a camera has ultimately determines how much light it uses to create an image. As noted in my post on APERTURE, capturing a great picture is not about selecting buttons and switches on a highly sophisticated camera or lens, it’s about seeing and capturing light. Without light, there is no photograph. In very simple terms, image sensors are the digital equivalent of film. They consist of millions of light-sensitive spots called photosites which are used to record information about what is seen through the lens. Therefore, it stands to reason that a bigger sensor can gain more information than a smaller one and produce better images. Able to gain more information, the large sensor would be capable of turning out photos with better dynamic range, less noise and improved low light performance over that of a smaller sensor.  Another thing to understand is that sensor size relates to capture size. As a sensor reduces in size, it captures image data from a smaller area than a 35 mm film SLR camera would, effectively cropping out the corners and sides that would be captured by the 36 mm × 24 mm 'full-size' film frame. This is called crop factor and is related to the ratio of the dimensions of a camera's imaging area compared to a reference format; most often, this term is applied to digital cameras, relative to 35 mm film format as a reference. The term crop factor was coined in recent years in an attempt to help 35 mm film format SLR photographers understand how their existing ranges of lenses would perform on newly introduced DSLR cameras which had sensors smaller than the 35 mm film format, but often utilized existing 35 mm film format SLR lens mounts.Because of this crop, the effective field of view (FOV) is reduced by a factor proportional to the ratio between the smaller sensor size and the 35 mm film format (reference) size. Another thing to understand is that sensor size relates to capture size. As a sensor reduces in size, it captures image data from a smaller area than a 35 mm film SLR camera would, effectively cropping out the corners and sides that would be captured by the 36 mm × 24 mm 'full-size' film frame. This is called crop factor and is related to the ratio of the dimensions of a camera's imaging area compared to a reference format; most often, this term is applied to digital cameras, relative to 35 mm film format as a reference. The term crop factor was coined in recent years in an attempt to help 35 mm film format SLR photographers understand how their existing ranges of lenses would perform on newly introduced DSLR cameras which had sensors smaller than the 35 mm film format, but often utilized existing 35 mm film format SLR lens mounts.Because of this crop, the effective field of view (FOV) is reduced by a factor proportional to the ratio between the smaller sensor size and the 35 mm film format (reference) size.So, larger sensors can help you capture better quality images, but as you can see from above, they bring with them a number of other characteristics, some good and some bad. Another obvious impact of a bigger camera sensor is that of size; not only will the sensor take up more room in your device, but it will also require a bigger lens to cast an image over it. Bigger sensors can also be better for isolating a subject in focus while having the rest of the image blurred. This usually meant a bigger and heavier camera, however, the good news here is that camera manufacturers are coming up with ways to put larger sensors into smaller cameras. | |

Types of Sensors: There are only two basic types of sensors, CCD and CMOS. CCD stands for ‘charge-coupled device’. CCD sensors are renowned for creating the highest quality, lowest noise images, however, they consume 100x the battery power of a CMOS sensor. CMOS stands for ‘complementary metal oxide semiconductor’. They are considerably cheaper to produce than CCD sensors and are faster at reading the information gathered when you open your shutter and expose it to light. Furthermore, they are known to suck up less power from your battery, thus enhancing battery life. Beyond this, sensors are classified by their physical size, which most often determines the size and classification of the camera that the are found in. Let’s review the options generally available. Types of Sensors: There are only two basic types of sensors, CCD and CMOS. CCD stands for ‘charge-coupled device’. CCD sensors are renowned for creating the highest quality, lowest noise images, however, they consume 100x the battery power of a CMOS sensor. CMOS stands for ‘complementary metal oxide semiconductor’. They are considerably cheaper to produce than CCD sensors and are faster at reading the information gathered when you open your shutter and expose it to light. Furthermore, they are known to suck up less power from your battery, thus enhancing battery life. Beyond this, sensors are classified by their physical size, which most often determines the size and classification of the camera that the are found in. Let’s review the options generally available. | |

| |

| |

| Summary: Obviously, many physical aspects contribute to making a quality picture; from the quality and speed of the lens and the number of its elements, the size of the sensor, the number of megapixels “crammed” onto the sensor, RAW capture, to the camera’s built-in ability to perform focusing, apply anti-shake, and algorithms designed to perform post “clean-up” of the image. One thing still remains true, the larger the image sensor is, as it relates to all of these aspects, the better the final result will be. |

Scanning Notes for My EPSON V100 Photo Scanner

| I created this page for my sole use, to remind me of things to remember when scanning pictures. If other viewers find anything useful here, great! |

Always scan at 300dpi and save the file as either a …

|

EPSON Flatbed Scanner Specs for my picture files:

|

Settings for Scanning a picture or Film Negative:

|

Sharing Options:

|

Understanding ISO

What is ISO? The three letters stand for International Organization for Standardization (ISO). ISO is one of the three pillars of photography referred to as the “Exposure Triangle” (the other two being Aperture and Shutter Speed) and every photographer needs to thoroughly understand it to get the most out of their equipment. It's one of the most prominently featured specifications of any modern digital camera, and it's one single aspect that can make a night-and-day difference in the outcome of your shots. So, what is it? ISO is the measure of your cameras’ digital image sensor’s sensitivity to available light. Unlike the old days when you literally had to change the film to change its sensitivity (formerly expressed as ASA), digital cameras allow you to just set the ISO as desired. Typically, ISO numbers start from 100-200 (Base ISO) and increment in value in geometric progression (power of two), e.g. 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200, 6400, etc. The important thing to understand here is that each step between the numbers effectively doubles the sensitivity of the image sensor. What is ISO? The three letters stand for International Organization for Standardization (ISO). ISO is one of the three pillars of photography referred to as the “Exposure Triangle” (the other two being Aperture and Shutter Speed) and every photographer needs to thoroughly understand it to get the most out of their equipment. It's one of the most prominently featured specifications of any modern digital camera, and it's one single aspect that can make a night-and-day difference in the outcome of your shots. So, what is it? ISO is the measure of your cameras’ digital image sensor’s sensitivity to available light. Unlike the old days when you literally had to change the film to change its sensitivity (formerly expressed as ASA), digital cameras allow you to just set the ISO as desired. Typically, ISO numbers start from 100-200 (Base ISO) and increment in value in geometric progression (power of two), e.g. 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200, 6400, etc. The important thing to understand here is that each step between the numbers effectively doubles the sensitivity of the image sensor. The higher the ISO, the more sensitivity and the greater the image sensor's light gathering capacity; meaning the less natural light that is needed to create the desired exposure. Though a higher ISO allows you to capture pictures in low light situations, the downside is that you will end up with increased image noise (more grainy). 100-200 ISO, usually the default setting, is generally accepted as ‘normal’ and will give you lovely crisp shots with very little noise/grain. Even though you should always try to stick to the base ISO in order to get the highest image quality, there will be times when working in low-light conditions that you will not be able to do so. Though most people tend to keep their digital cameras in ‘Auto Mode’ where the camera selects the appropriate ISO setting depending upon the conditions you’re shooting in, there may be advantages to selecting your own ISO. The higher the ISO, the more sensitivity and the greater the image sensor's light gathering capacity; meaning the less natural light that is needed to create the desired exposure. Though a higher ISO allows you to capture pictures in low light situations, the downside is that you will end up with increased image noise (more grainy). 100-200 ISO, usually the default setting, is generally accepted as ‘normal’ and will give you lovely crisp shots with very little noise/grain. Even though you should always try to stick to the base ISO in order to get the highest image quality, there will be times when working in low-light conditions that you will not be able to do so. Though most people tend to keep their digital cameras in ‘Auto Mode’ where the camera selects the appropriate ISO setting depending upon the conditions you’re shooting in, there may be advantages to selecting your own ISO. |

Noise: Digital noise in photos taken with digital cameras is random pixels scattered all over the photo that degrades the photo quality. Digital noise usually occurs when you take low light photos (such as night photos or indoor dark scenes) or you use very slow shutter speeds or very high sensitivity modes. Image noise is random (not present in the object imaged) variation of brightness or color information in images, and is usually an aspect of electronic noise. Produced by the image sensor and circuitry of a digital camera, it is the undesirable by-product of image capture that adds spurious and extraneous information. Think of it as analogous to the subtle background hiss you may hear from your audio system at full volume. For digital images, this noise appears as random speckles on an otherwise smooth surface and can significantly degrade image quality. Although noise often detracts from an image, it is sometimes desirable since it can add an old-fashioned, grainy look which is reminiscent of early film. Some noise can also increase the apparent sharpness of an image. Noise increases with the sensitivity setting in the camera, length of the exposure, temperature, and even varies at the same settings on different camera models. A sharp noisy picture is far better than a blurry fine grained one or no picture at all. Digital noise can be dealt with using a combination of optimizing the camera settings and by removing it with professional software. Noise: Digital noise in photos taken with digital cameras is random pixels scattered all over the photo that degrades the photo quality. Digital noise usually occurs when you take low light photos (such as night photos or indoor dark scenes) or you use very slow shutter speeds or very high sensitivity modes. Image noise is random (not present in the object imaged) variation of brightness or color information in images, and is usually an aspect of electronic noise. Produced by the image sensor and circuitry of a digital camera, it is the undesirable by-product of image capture that adds spurious and extraneous information. Think of it as analogous to the subtle background hiss you may hear from your audio system at full volume. For digital images, this noise appears as random speckles on an otherwise smooth surface and can significantly degrade image quality. Although noise often detracts from an image, it is sometimes desirable since it can add an old-fashioned, grainy look which is reminiscent of early film. Some noise can also increase the apparent sharpness of an image. Noise increases with the sensitivity setting in the camera, length of the exposure, temperature, and even varies at the same settings on different camera models. A sharp noisy picture is far better than a blurry fine grained one or no picture at all. Digital noise can be dealt with using a combination of optimizing the camera settings and by removing it with professional software. |

Noise Reduction: Always a factor is the amount and type of noise reduction being applied in the camera. Because all pixels collect some noise, every digital camera runs processing on every image (except for a RAW file that can be changed later) to minimize that noise. Newer cameras use newer technology to reduce that noise, with the result being less noise at similar ISOs than what earlier cameras could achieve. Improvements in this area have been huge in recent years.The second thing to remember is that many post editing programs offer functions for reducing noise. If it is a matter of choosing between not being able to take a picture and suffering with a noisy image, I'd rather be able to take the picture at a higher ISO and then try to clean up the noise afterwards in a noise reduction software. Noise Reduction: Always a factor is the amount and type of noise reduction being applied in the camera. Because all pixels collect some noise, every digital camera runs processing on every image (except for a RAW file that can be changed later) to minimize that noise. Newer cameras use newer technology to reduce that noise, with the result being less noise at similar ISOs than what earlier cameras could achieve. Improvements in this area have been huge in recent years.The second thing to remember is that many post editing programs offer functions for reducing noise. If it is a matter of choosing between not being able to take a picture and suffering with a noisy image, I'd rather be able to take the picture at a higher ISO and then try to clean up the noise afterwards in a noise reduction software. |

ISO Speed & Image Sensor Size: The size of the image sensor determines the ISO speed range that a digital camera can use without suffering from undue noise. One reason for this is because the pixels on the larger image sensor can be larger and therefore receive more light, and thus have a greater signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio. Simply put, if you have two image sensors, each with 4 megapixels resolution, but of different sizes, the 4 megapixels image sensor that is smaller will exhibit more noise at higher ISOs than the larger one. 4 million tiny pixels crammed into a 1/1.8 in. image sensor cannot compete in image quality with 4 million large pixels on an APS-sized image sensor. Most consumer digital cameras use 1/1.8 in. (and smaller) image sensors, so noise at high ISO is more of a problem. A digital SLR (dSLR), on the other hand, uses a large image sensor, usually full frame (24x36 mm) or APS-sized (half-frame). Noise is rarely a problem and the use of a high ISO 400 results in images with barely noticeable noise. Even as manufacturers attempt to bridge the gap between consumer and professional digital cameras by using a slightly larger image sensors, the "megapixels race" has meant that ever more pixels are being crammed into a small area. Where before there were 5 million pixels on a 2/3 in. image sensor, now we see 8 million pixels crammed on the same sized image sensor. It is therefore not surprising that noise remains a problem. And which is why you should not be fooled by the "more megapixels is better" mantra. ISO Speed & Image Sensor Size: The size of the image sensor determines the ISO speed range that a digital camera can use without suffering from undue noise. One reason for this is because the pixels on the larger image sensor can be larger and therefore receive more light, and thus have a greater signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio. Simply put, if you have two image sensors, each with 4 megapixels resolution, but of different sizes, the 4 megapixels image sensor that is smaller will exhibit more noise at higher ISOs than the larger one. 4 million tiny pixels crammed into a 1/1.8 in. image sensor cannot compete in image quality with 4 million large pixels on an APS-sized image sensor. Most consumer digital cameras use 1/1.8 in. (and smaller) image sensors, so noise at high ISO is more of a problem. A digital SLR (dSLR), on the other hand, uses a large image sensor, usually full frame (24x36 mm) or APS-sized (half-frame). Noise is rarely a problem and the use of a high ISO 400 results in images with barely noticeable noise. Even as manufacturers attempt to bridge the gap between consumer and professional digital cameras by using a slightly larger image sensors, the "megapixels race" has meant that ever more pixels are being crammed into a small area. Where before there were 5 million pixels on a 2/3 in. image sensor, now we see 8 million pixels crammed on the same sized image sensor. It is therefore not surprising that noise remains a problem. And which is why you should not be fooled by the "more megapixels is better" mantra. |

Choosing An ISO Setting: The result of the sensor’s increased sensitivity due to higher ISO settings, means that it needs less time to capture an image. When you do decide to override your camera and choose a specific ISO you’ll notice that it impacts the aperture and shutter speed needed for a well exposed shot. For example – if you bumped your ISO up from 100 to 400 you’ll notice that you can shoot at higher shutter speeds and/or smaller apertures. What does this mean? if your camera sensor only needed exactly 1 second to capture a scene at ISO 100, simply by switching to ISO 800, you can capture the same scene at 1/8th of a second or at a shutter speed of 1/125 sec. That can mean a world of difference in photography, since it can help to freeze the motion of a subject that would otherwise end up being blurred when shot at ISO 100, thereby ruining the shot. When should you increase ISO? … Choosing An ISO Setting: The result of the sensor’s increased sensitivity due to higher ISO settings, means that it needs less time to capture an image. When you do decide to override your camera and choose a specific ISO you’ll notice that it impacts the aperture and shutter speed needed for a well exposed shot. For example – if you bumped your ISO up from 100 to 400 you’ll notice that you can shoot at higher shutter speeds and/or smaller apertures. What does this mean? if your camera sensor only needed exactly 1 second to capture a scene at ISO 100, simply by switching to ISO 800, you can capture the same scene at 1/8th of a second or at a shutter speed of 1/125 sec. That can mean a world of difference in photography, since it can help to freeze the motion of a subject that would otherwise end up being blurred when shot at ISO 100, thereby ruining the shot. When should you increase ISO? …

|

| Summary: You already know it is tough to shoot good digital photos in low light conditions without a flash. The trick is really to get more light into the camera without using that harsh flash – and we can do that by cranking up the ISO setting to the higher part of the range and setting the camera to Aperture Priority (an f-stop (bigger aperture) that allows more light through. It also helps to shoot in RAW mode so that you capture maximum detail in your digital shot (no compression in the captured image). ISO is an important aspect of digital photography to have an understanding of if you want to gain more control of your digital camera. A solid understanding of ISO and experimenting with different settings and how they impact your images will help you make smarter decisions about how to set your camera that, in turn, will lead to better pictures. |

Taking Better Pictures with a Cell-Phone

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)